A Look Inside the Films of Federico Fellini

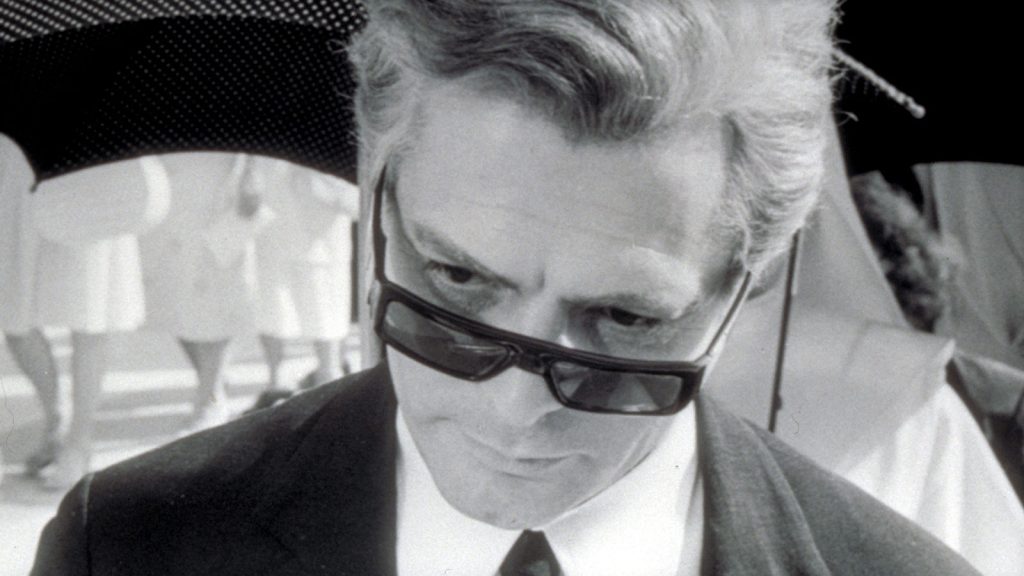

During the late 1940s and the 1950s in Italy, it was all about Neorealism, which was a style of filmmaking Italian directors developed after World War II. Italian Neorealism was based on the issues Italians faced after the war and was known for the use of nonprofessional actors. Federico Fellini followed in this Neorealism trend and focused his first films on post WWII Italy, especially the poor and the struggles they had to deal with in that time period. His neorealist phase was influenced by Roberto Rossellini, who Fellini worked with writing films in the late 1940s. In his six year neorealist phase lasting “from 1950 to 1956” he directed great movies like La strada (1954) and I vitelloni (1953) (Kauffmann, 28). Fellini then began to transition into a different style of filmmaking, a style that would put him on the map for a very long time. During this later phase he developed a style in which many themes could be found from the character’s search for love, happiness and meaning, to being intensely personal, to being episodic and picaresque. Fellini was a perfectionist and he knew what he wanted from his actors and during his career he coined a term called “felliniesque” which is a style of filmmaking that perceives dreams and reality as one experience. In Fellini’s later phase his style really came out in his films such as 8 ½ (1963), Juliet of the Spirits (1965), and Casanova (1976). The idea of blending reality and dreams into one experience is a theme that can be traced through Federico Fellini’s work.

Reality and Dreams

The concept of perceiving reality and dreams as one experience is certainly not a new idea for Fellini and his films. Fellini himself lived in his own world inside his head and was constantly creating new ideas based on his own personal experiences. Fellini would go through life and encounter something that triggers his fantasy and he “[created] characters and situations that seem to organize themselves” (Bachmann, 3). He was a strong believer in cinema that came from life rather than life that comes from cinema. The idea of perceiving reality and dreams as one experience is best described through his films. Fellini’s 8 ½ (1963) is the ideal image of this concept as well as a good example of his style, “felliniesque.” 8 ½ focuses on a worn out film director named Guido Anselmi (Marcello Mastroianni) who drifts away in his own head when the pressure of making a new film becomes too much for him to handle.

Fellini portrays himself as a man of imagination and a man searching for love, true happiness and meaning. He also presents a fine line between reality and imagination, he wants to perceive reality as it is in his dreams but his imagination is much bigger than reality allows. The whole idea of 8 ½ is to show people a surreal reality, it is a story that reflects Fellini and no one can have Fellini without his dream life. Being somewhat of an autobiography, Fellini uses Marcello Mastroianni to mirror himself and create his alter ego. The character of Guido in 8 ½ also experiences the writer’s block Fellini himself was experiencing at the time the film was made. According to James Monaco “8 ½ remains [a] key Fellini movie because it is freer from the tyranny of narrative than anything that came before or since” (46). The breaking away from the normal narrative helps pave the way for Fellini’s imagination and his character Guido. This different narrative plot is defined by “Guido’s [own] narratives [moving] from dreams to memories to fantasies to screen-tests and then to visions which are beyond private fantasy” (Burke, 165). Fellini’s use of Guido’s dreams and fantasies helps contrast the harsh reality he is facing such as the public scrutiny he is experiencing in the mists of his new film. Guido’s dreams are more along the lines of self-reflective nightmares, rather than pleasant dreams. Naturally dreams/nightmares are unconscious thoughts experienced in one’s sleep that they have no control over. Instead of forgetting them, Guido does the opposite and allows them to “narrate him rather than vice versa” (Burke, 165). But compared to memories, which are naturally conscious, Guido is able to control the memories in a way. Fellini’s main focus is Guido’s fantasies which are presented as “a realm of pure wish fulfillment in the present” moment in which he is experiencing (Burke, 165). These are the parts Fellini uses to perceive reality and dreams/fantasies (in Guido’s case) as one experience.

The character of Guido falls in and out of fantasy all throughout the film, for instance at the beginning of the film Guido sees a beautiful woman in the field next to the venue where he is meeting a writer and she runs elegantly toward him to hand him a glass of water, she smiles and then he realizes its just an average water woman and nothing more. Another example is the extravagant carnival fantasy ending, where all the dreams, memories and fantasies come together. Guido sees what he wants to see and Fellini achieves this by blending the two elements perfectly together. After moving from dreams to memories to fantasies, it finally reaches the screen-tests. Unlike the images before, the screen-tests can be controlled and planned and “they reflect Guido’s attempts to create not just a momentary vision but an entire fictional world: a movie” (Burke, 165). This is something Fellini himself creates in a number of his films to elaborate on his own mind and imagination. For Fellini making a film was an art and he used life to inspire his art and it was his way of creating a fictional world. 8 ½ was one of Fellini’s best films because it let the audience know what he struggles with in his own personal life as well as what he struggles in the process of making new films.

After 8½ was released Juliet of the Spirits came out and it was Fellini’s first full-length color feature about loneliness, dreams and spirits. Juliet of the Spirits is about an Italian housewife (Giulietta Masina) who lives a mundane life with her husband (Mario Pisu) and she starts realizing she wants more out of her life. Juliet’s friends throw a party for her at the beginning of the film and they “bring a medium to [her] house, who summons a woman’s spirit to speak to her” (Kauffmann, 28). The sequence opens up Fellini’s realm of fantasy for Juliet and her subconscious. The use of the mediums throughout the film gives the illusion of reality and fantasy as a single experience. The encounters with the mediums and the spirits are meant to make Juliet explore her fantasy and help her understand the present tense by opening a more complex world. Unlike Guido in 8 ½, Juliet’s “fantasies and fantastic adventures seem unrelated to her” and do not control her like they did with Guido (Kauffmann, 29). This effect does not really take away from Fellini’s cinematic flow of fantasy and reality as one experience. Juliet’s dream and recollection scenes are intertwined with her harsh reality and the difficulties she is facing. By the end of Juliet of the Spirits, Juliet has freed herself from the things that had been holding her back. Fellini captured her in the perfect moment, walking away from the problems of the past as a single free woman.

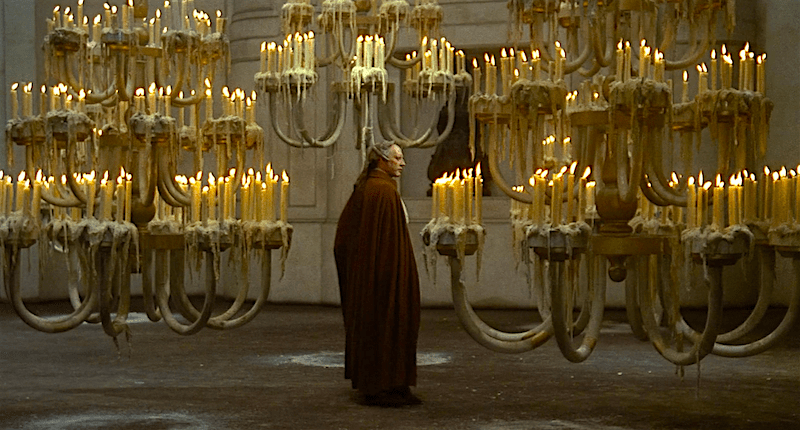

Fellini’s Casanova (1976), although highly criticized by some, remains a crucial film in his career because of its extensive use of sexual imagination and dreams. Fellini did not like to adapt literary works from other writers but Casanova was one of a few films Fellini made that was not solely based on his own imagination. It was adapted from the autobiography of an 18th century writer and adventurer named Giacomo Casanova (Donald Sutherland). A character Fellini did not really like and it could be seen throughout the film. By the end of the movie, he realizes Casanova’s struggle with love and happiness, something Fellini also struggled with, and in the final scene it all comes together. To give the illusion of perceiving reality and dreams, “Casanova begins with fireworks illuminating the waters of the Grand Canal [in Venice] and ends, in the aged Casanova’s dream, with the Canal frozen over; it begins, in other words in heat and life and ends in cold and death” (Willis, 27). The dream ending, in a way, gives Casanova a small sense of sympathy from the audience even though he has learned absolutely nothing. Casanova’s imagination makes the film, and the dream sequence is one of the most powerful scenes in the movie and it does not, “depend on dialogue, but on movement, noise and music” (Willis, 29). A dream is solely based on what is happening rather than the conversations going on and this end scene is by far the most telling scene for Fellini. Some critics believe the end scene made the movie and pulled all the elements together. Like many of Fellini’s films, Casanova is given that carnival atmosphere and it helps create that sense of reality and dreams as a single experience. The use of carnivals can be traced through many of his films and he wasted no time in Casanova by placing it in the opening scene. The carnival atmosphere helped produce Casanova’s imaginative forces that are present throughout the movie. It seems as if Casanova being the man he is has two imaginations, a sexual and a romantic. Throughout the entire film the audience is given that illusion of dreams and reality in the end by using Casanova’s romantic imagination. With the end in Casanova’s romantic imagination (the dream), Fellini is able to achieve the same idea that was presented at the beginning of the film.

Everything is Personal

There are many themes that make up Fellini’s “felliniesque” style and one of them is the idea of being intensely personal. After breaking away from Italian Neorealism Fellini’s “best films have been about himself in his new world, directly (8 ½) or indirectly (Juliet of the Spirits)” (Kauffmann, 29). A number of his films are self-reflective and he pulls elements from his life to create his films and 8 ½ is the perfect example of this theme. Not only is the film about a director experiencing writer’s block but he is also experiencing problems with his wife. During the film the audience is shown a number of Guido’s fantasy woman as well as his own mistress, Carla (Sandra Milo). Compared to Guido’s wife (Anouk Aimée) Carla is an over the top, high class woman who loves expensive dresses and clothes, Luisa on the other hand is a simple quiet woman. She found out about Guido’s affair with Carla three years prior to the time the film was taking place. Luisa disregarded the affair and continued to live Guido’s lie but at the end of 8 ½ she told Guido she is tired of living his lies and she wants the whole world to know who he really is. After his new film production falls apart Guido realizes he has freedom and he realizes he wants to tell the truth and look into Luisa’s eyes without shame anymore. This dramatic ending might not be directly linked to Fellini’s life but some critics believe 8 ½ truly reflects Fellini’s struggle with his wife, Giulietta. Both problems with his wife and his new film also occurred in Fellini’s life at one point and he uses them in his films.

In relation to his personal life and his struggle with his wife, Fellini uses Giulietta Masina in a number of his films, some of which are directly or indirectly self-reflective. Despite being “attacked by feminist critics for his exuberant portrayal of well-endowed women who populate a fantasy world of Fellini’s own creation,” the relationship between him and Giulietta lasted until his last day (Bondanella, 50). It was in Juliet of the Spirits (1965) when Fellini drew strong parallels between Juliet, played by Giulietta, Giorgio and himself. It is no doubt that the character of Giorgio has a lot of similarities to Fellini himself. Giorgio is the unfaithful, deceitful husband, while Juliet (which is Giulietta in Italian) is the loyal housewife at the beginning. Some critics believe it is “Fellini’s act of contrition to his wife” (Bondanella, 48). Fellini’s obsession with women did not stop there it continued throughout his career and it is no shock that he decided to direct Casanova, a film about a man searching for sex, love and women. This search for love and women was not a new concept for Fellini because it was also an element of interest in his most self reflective film, 8 ½. In Casanova, the main theme is about the search for love and as much as he wants to find it he only finds real satisfaction in sex rather than love leaving him to feel empty inside. After looking into Fellini’s films Stanley Kauffmann believed that “if Casanova, the very choice of Casanova, can be read in any illuminating way, it’s as a confession, almost trusting confession, of emptiness” (29). Fellini lived life the way he wanted and at some points he did get lost just like his characters and he does experience that feeling of emptiness. Throughout his films, Fellini questions the meaning of life and whether or not one thing-like love or happiness- is worth it all.

Characters search for love, happiness and meaning

Unlike Italian Neorealism, Fellini’s new style focused on the characters search for love, happiness and meaning rather than the struggles of a poor person’s everyday life. Throughout his career, Fellini portrayed all of his characters as being lost and their overwhelming desire to find something worth meaning. In 8 ½, Guido is constantly searching for love, happiness and meaning. His directing career is slowly dissolving, due to the writer’s blocker, as well as his relationship with his wife. Fellini uses Guido’s nightmares to reflect “his relationship with Carla and, in particular, his repressed guilt about that relationship” (Burke, 165). After realizing the guilt, Guido attempts to find love again. In the mists of the love and guilt he is dealing with his career falling apart and the pressure to make a new movie. That leads to the search for meaning because he wonders what he is without films. After Luisa, his wife, walks out on him Guido begins to question the movie and ultimately his life. He is a man that wants everything and he does not want to miss out on anything. By the end, however, he explains to Luisa that people should accept him the way he is if they can. He also tells her that she is his true love and how she is his salvation. Finding salvation was also something in he was searching for through his making of a new film. But in the end Guido, in a way, is given freedom and realization.

Juliet from Juliet of the Spirits also experiences the search for love, happiness and meaning. After finding out about her husband’s affair, Juliet ventures out of the house and meets other women who offer her a number of different choices as a woman. These new perspectives make Juliet realize “none of these choices [seem] to be acceptable, and she is torn apart by her inability to know what her future should be” (Bondanella, 49). Like most of Fellini’s characters Juliet has been thrown into a situation where she needs to find herself. Casanova is another character in the same search as Guido and Juliet, although his end results show he did not learn anything from his experiences. Although the places he was search for love, happiness and meaning turned out to be the wrong places. Even though the results of Casanova’s experiences were not as successful as Guido or Juliet, Fellini leaves the characters uncertain of the future. In an interview with Fellini, he said “I don’t have any certainty or clarity myself; it would be dishonest to give the characters of my movies” (Peri, 32). Fellini gives realistic endings, the search for love, happiness and meaning is never really over.

Episodic and Picaresque

Along with being intensely personal and centered around fantasy, Fellini made his films to be episodic and picaresque. Fellini likes to think of himself as an artist and therefore his art needs to express who he is which is why he makes picaresque films. A picaresque film includes a roguish character on an episodic journey to find true happiness and meaning. Casanova and Guido are the perfect roguish characters on an episodic journey. Casanova is a dishonest adventurer that travels across Europe in an endless search for sex and women. According to Don Willis “Casanova, on one level, is a network of such resonances, or afterimages, that crisscrosses and merges with the dramatic or episodic level, and finds meaning in and gives meaning to it” (26). Casanova’s episodic level emphasizes his sexual desires as well as sex itself, moving from country to country falling in and out of “love.” Guido on the other hand is dishonest filmmaker on a journey that ends with a realization that is not really realized. The intertwining of reality and dreams help break up the episodic journey moving from dreams to memories to fantasies, all of which are experienced while dealing with reality. Both Casanova and Guido create the picaresque world of Fellini’s films.

Federico Fellini’s film career will continue to inspire many directors in the future. His wild imagination and use of picaresque images will undoubtedly keep his name on the charts for a many years to come. Even though Fellini started off with the idea of Italian Neorealism, he was meant for something different, something artistic. He was meant for something that represented him and an extravagant dream life. Fellini once said “the stories are born in me, in my memories, in my dreams, in my imagination” and his films reflect this concept of blending these three perspectives (Bachmann, 3). Throughout his career Fellini lived to present his fantasies and imagination through art and nothing else.

“There is no end. There is no beginning. There is only the infinite passion of life. ”

Federico Fellini

Bondanella, Peter. “Juliet of the Spirits.” Cineaste (2002): 48-50. Print.

Burke, Frank. “Modes of Narration and Spiritual Development in Fellini’s 8 1/2.” Literature Film Quarterly 14.3 (1986): 164. Film & Television Literature Index. EBSCO. Web. 18 Oct. 2010.

Fellini, Federico, and Gideon Bachmann. “A Guest in My Own Dreams: An Interview with Federico Fellini.” Film Quarterly 47.3 (1994): 2-15. Print.

Kauffmann, Stanley. “8 1/2 — Ladies’ Size (Film).” New Republic 153.20 (1965): 28-32. Film & Television Literature Index. EBSCO. Web. 13 Oct. 2010.

Kauffmann, Stanley. “Fellini’s Casanova.” New Republic 176.10 (1977): 28-29. Film & Television Literature Index. EBSCO. Web. 13 Oct. 2010.

Monaco, James. “Federico Fellini’s 8 1/2.” Cineaste 27.3 (2002): 46. Film & Television Literature Index. EBSCO. Web. 13 Oct. 2010.

Peri, Enzo, and Federico Fellini. “Federico Fellini: An Interview.” Film Quarterly 15.1 (1961): 30-33. Print.

Willis, Don, and Albert Johnson. “Two Views On: Fellini’s Casanova.” Film Quarterly 30.4 (1977): 24-31. Print.